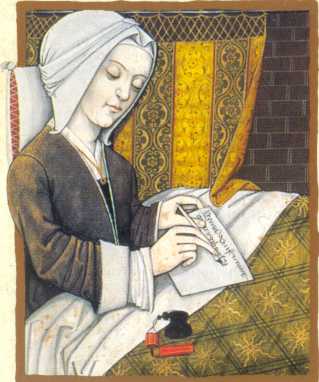

Christine de Pizan was born in Venice between 1364 and 1365. Her father was Tommaso di Benvenuto da Pizzano— the last part of his name, Pizzano, refers to his home town of Pizzano, a small village to the southeast of Bologna. Christine de Pizan hard at work, inCollected Works of Christine de Pisan, 1410-1411Di Benvenuto da Pizzano was a well-educated man, who had served as a professor of the University of Bologna (one of the leading education hubs of the world) and had subsequently taken a post in the Venetian Court. But not long after Chritine’s birth, Tommaso accepted a post in Charles V’s Court. He became the French court’s astrologer. By 1368, the Pizzano family had relocated to Paris.

Christine de Pizan was born in Venice between 1364 and 1365. Her father was Tommaso di Benvenuto da Pizzano— the last part of his name, Pizzano, refers to his home town of Pizzano, a small village to the southeast of Bologna. Christine de Pizan hard at work, inCollected Works of Christine de Pisan, 1410-1411Di Benvenuto da Pizzano was a well-educated man, who had served as a professor of the University of Bologna (one of the leading education hubs of the world) and had subsequently taken a post in the Venetian Court. But not long after Chritine’s birth, Tommaso accepted a post in Charles V’s Court. He became the French court’s astrologer. By 1368, the Pizzano family had relocated to Paris.

It was in the Parisian Court that Christine de Pizan began her education. Though there is no clear evidence as to how Pizan would transform herself into a professional writer, facts about her social world offer hints. For example, her father played an important role in the court and had access to Charles V’s library and archive, which was considered to be the best in the world. He seems to have encouraged her learning and maybe even furnished her access to books and manuscripts.

Christine de Pizan was married at the tender age of fifteen to Etienne du Castel, who was the Royal Secretary to the Court. Having a secretarial post meant that du Castel’s was both an intellectual and highly literate as well as someone who was in the early stages of a promising political/courtly career. Although their marriage was arranged, their martial union seems to have been a happy one. Castel allowed Pizan to continue her education and her learning of classical texts as well as languages. Through their marriage, Pizan and Castel had three children, but only two survived to adulthood.

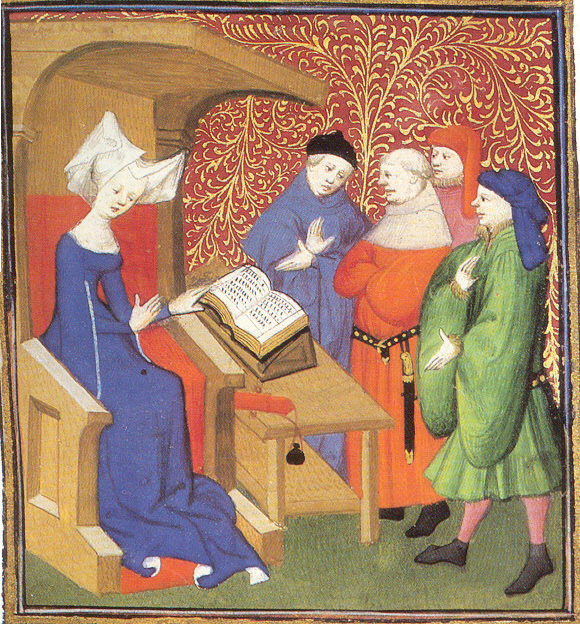

Chritine de Pizan Instructing her Son, in

Chritine de Pizan Instructing her Son, in

Collected Works of Christine de Pisan, 1410-1411

Personal tragedy struck Christine in 1390 when Etienne died suddenly as he visited Beauvais on a courtly assignment. Widowed at twenty-five, Christine de Pizan was left with almost no means to support her young children, niece, and mother. She tried in vain to collect her husband salary and even gather money from her estate, but both of these procedures were embattled in the courts and took over fourteen-years to resolve. Well-educated and knowledgeable, she turned to the pen as a way to provide for her family.

In the late 1390s, women writers were considered a novelty and a rarity. But her works quickly gained support in the Paris Court. Royal and wealthy patrons, intrigued by Pizan’s abilities, hired her to compose ballads, songs, and poems. Love, courtly life, and the exploits of her wealthy patrons were the most common subject matter of Pizan’s work. Her popularity soared and she gained the regular patronage of important royals, such as the Queen Isabeau of Baviere, the Duke of Burgundy, and the Duke of Berry. She worked consistently from 1393 to the mid-1410s, writing hundreds of poems, ballads, essays, and songs.

In 1402, the tone of her work change. Pizan engaged in a literary Débat (debate) with Roman de la Rose, a well-known thirteen-century text that was extremely misogynistic and portrayed women as nothing more than seductive temptresses. In Les Epistres sur le Roman de la Rose, Pizan argued against the fallacies promulgated by this older-text and for the capacities of women (Desmond, 2003). Pizan would further articulate her argument about women’s virtue in Le Livre de la Cité des Dames written in 1405. This book would become her more renowned and influential work. Through these texts she positioned herself as a defender of women’s capacities, virtues, and influences (Bell, 1976, 3-4). As a capable and eloquent writer, Pizan was an embodiment of the very womanhood she praised.

Christine de Pizan’s last known work was published in 1429 and it was a long poem celebrating Joan of Arc’s accomplishments. In her illustrious career, she wrote on a wide array of topics: morality, feminist defense, religion, literary commentary, and even politics. Through her writings, she was able to meet her family’s every need and maintain a respected position within the Court. She died when she was in her late sixties in 1430.

Pizan is considered one of the first women to make a living as a professional writer (Bell, 20046, 164). Her works, especially her defense of women’s virtues, continued to be read and discussed well-after her death. In 1949’s Épître au Dieu d'Amour, leading French writer and feminists Simone de Beauvoir credited Chrisitne de Pizan’s writing as “the first time we see a woman take up her pen in defense of her sex” (de Beauvoir, 1949, 111). Pizan had profound influential of courtly writings, especially on how women would be discussed and represented in literature.

.jpg)